I’ve been arguing all through this newest inflationary episode that the central financial institution charge hikes had been really introducing inflationary pressures by means of a variety of channels, essentially the most notable one within the Australian context being the rental element within the Shopper Value Index. The RBA has categorically denied this perversity of their coverage method, and, as an alternative, claimed the quickly escaling rental inflation was the results of a decent rental market, finish of story. Effectively the rental market is tight, largely because of the huge cutbacks in authorities funding in social housing over the previous couple of many years. However the rental hikes adopted the RBA charge hikes and the easy cause is that landlords when in a decent market will at all times cross on the prices of their funding mortgages to the tenants. They weren’t doing that earlier than the speed hikes. A latest ECB analysis report – How tightening mortgage credit score raises rents and will increase inequality within the housing market (printed January 16, 2025) – offers some sturdy proof which helps my argument. That’s what this weblog put up is about.

The ECB analysis report notes that:

Housing affordability is a sizzling matter in lots of euro space nations. Steadily growing rents and traditionally excessive home costs are forcing many households – notably younger folks and city-dwellers – to commit ever extra of their earnings to housing[

The same can be said for Australia.

The latest – Housing Affordability Report (released in November 2024) – by ANZ-CoreLogic shows that:

Affordability metrics have worsened, with the median dwelling value-to-income ratio rising to 8.0. Median income households needed 10.6 years to save a 20 per cent deposit.

Other data (cited in the Report) shows that:

1. Gross median household income rose 2.8 per cent in the year to September 2024, while median housing values rose 8.5 per cent and rents rose 9.6 per cent over the same period.

2. The 20-year average dwelling value to income ratio in Australia was 6.7 and by September 2024 it was 8.

3. The 20-year average “years to save a 20% deposit” was 9 and by September 2024 it was 10.6.

4. The 20-year average “% of income required to service a mortgage” was 36.6 per cent and by September 2024 it was 50.6 per cent.

5. The 20-year average “% of income required to pay rent” was 29 per cent and by September 2024 it was 33 per cent.

6. “Modelling for September 2024 shows only 10% of the housing market would be genuinely affordable (require less than 30% of income to service a loan)2 for the median income household. This is well down on the 40% of Australian homes that were affordable for the median income household in March 2022.”

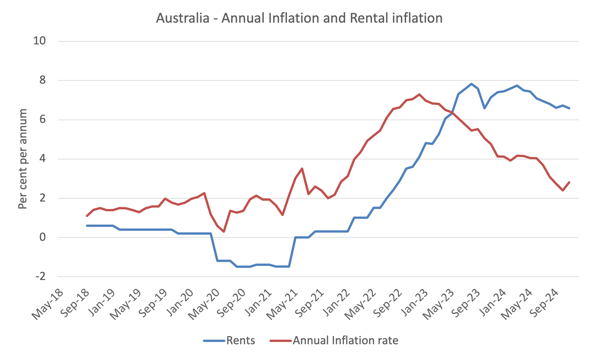

The rent inflation is also running faster than the overall inflation rate and is now causing persistence in the overall rate.

The following graph shows this for Australia.

Note that the so-called ‘tight rental market’ (the RBA diversion ‘speak’) was tight well below the acceleration in rents in the first part of 2022.

The dip in rental inflation during the early years of COVID was because fiscal policy provided rent relief – another demonstration as to how expansionary fiscal intervention is anti-inflationary rather than the opposite.

We are now seeing that effect in the electricity relief schemes in Australia which have countered the price gouging by the privatised electricity providers.

But what happened that period?

The RBA started hiking interest rates and the acceleration in rental inflation then took off.

The ECB Report considers another aspect of central bank policy in this regard.

They note that when the monetary authorities tightened “credit conditions by introducing limits to mortgage debt for banks or for borrowers” to cool housing inflation, the reduced access to mortgage credit reduced the “welfare for renters and prospective buyers.”

The policy had two broad effects:

1. “The wealthier households can opt for a cheaper property than they originally planned – perhaps smaller, of lower quality or in a cheaper area – reducing the amount they borrow to satisfy the tighter constraints.”

2. “However, those already hunting for more affordable properties may find themselves priced out of the market altogether. Therefore, they stay tenants for longer, either buying property later in life or not at all.”

These shifts push up the demand for rental accommodation but then the problem becomes a lack of suitable rental accommodation.

To “entice new investors into the market, rents will have to go up.”

There are equity and wealth implications arising with “a shift from owning your own home to renting and a concentration of housing ownership among the rich.”

The ECB researchers then tried to quantify how “limits to mortgage credit impact house prices and rents”.

They found that “borrowing limits increase rental prices. They are 4% higher four years after the intervention” but that the “house prices are virtually unchanged”.

There is a redistribution of home ownership as a result of the increasing “ownership concentration in the housing market” as the wealthier cohorts hoover up the housing stock while the lower-income families are pushed into rental accommodation that becomes more expensive.

I have consistently noted that the RBA rate hikes are having the same effect and facilitating a massive redistribution of income and wealth to the already high-income cohorts from the low-income cohorts.

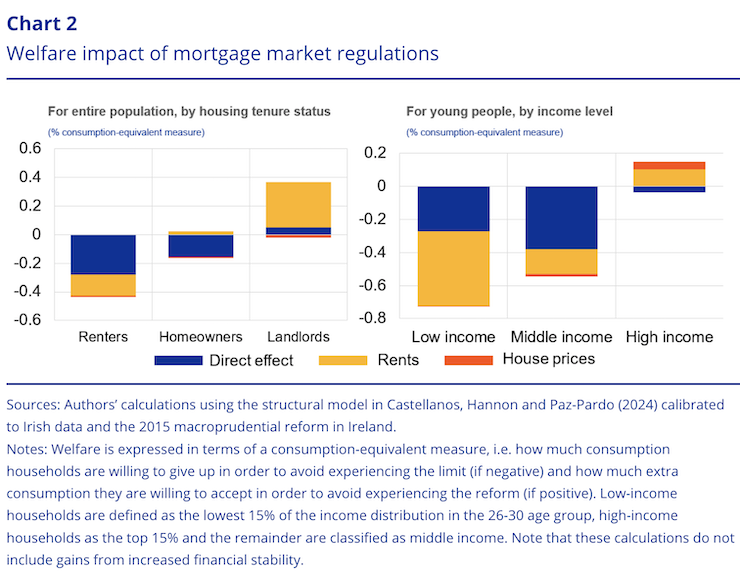

The ECB graph the distributional consequences of reducing the capacity of people to purchase homes, which can be done through credit controls – their example, or through rate hikes.

Here is their Chart 2, which shows that:

… the biggest losers are those who are not currently homeowners and will need credit to access homeownership. They are mostly young households in the lower or middle part of the income distribution.

The measure used to assess welfare is “a consumption-equivalent measure” which you can understand in terms of “how much consumption households are willing to give up in order to avoid experiencing the limit (if negative) and how much extra consumption they are willing to accept in order to avoid experiencing the reform (if positive).”

The research shows that the credit restrictions have negative welfare effects for the renters the largest effects come from the higher rents that impact on low-income households.

Current owner-occupiers are largely unaffected while landlords benefit greatly as a result of the higher rents that follow the central bank intervention.

The interesting part of the research from my perspective (in terms of being able to directly apply it to the Australian situation) was their assessment of the impact of higher interest rates on rental inflation.

They found that:

Overall, we find similar effects to those of the tighter credit limits: rents rise, house prices go down and homeownership rates drop.

Which establishes that rate hikes are inflationary as MMT economists have been arguing for some time in the face of the denial of mainstream monetary economists, who assert, without foundation the opposite.

The ECB research found some significant differences between the impacts of credit rationing and rate hikes.

1. “the rate hike makes saving in financial assets more attractive relative to investing in housing. As a result, rents need to go up even further to keep small housing investors in the market.”

2. “higher interest rates also make it easier to save for a downpayment, though we find this effect is minimal so tenants are still worse off.”

The ECB conclude that higher interest rates:

… have a direct impact on rents that can dampen the cooling effect of monetary policy on inflation as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices, as rents form a part of households’ consumption baskets.

And there you have it.

RBA denials

The RBA recently released a chapter in the RBA Bulletin (October 2024) – Do Housing Investors Pass-through Changes in Their Interest Costs to Rents? – that denied that interest rates hikes caused rental inflation.

They note that “Rent is the second largest component of the Consumer Price Index” .

In the RBA’s policy model, rents just “reflect the balance of demand for, and supply of, available housing”, which is the mainstream economic view.

So no allowance for price gouging by landlords or for landlords passing on higher borrowing costs.

They clain that the observation that interest rates and rental inflation tend to move together is just because in times of rising prices, which corresponds to rising spending pressures both the demand for rental accommodation rises and the central bank hikes rates to reduce inflationary pressures.

As a result:

So the observation that rates and rents move together may be a case of correlation, rather than higher rates causing higher rents.

But the RBA article ignores two important things about the current situation:

1. The inflationary pressures were not largely not an excess demand event but rather were the result of supply constraints arising from Covid restrictions and illness, the Putin escapade in the Ukraine, and some OPEC+ price gouging.

So the bouyant demand effect they talk about impacting on the demand for rental accommodation was not part of this story.

2. The “correlation” is somewhat blurred by the lagged response of rental inflation to the overall inflation rate.

As the graph shows, the inflation rate was rising before the rental inflation accelerated (as the supply constraints started to bind) and then the RBA hiked rates, and then rental inflation took off.

Another problem with the RBA study is that it uses data from 2006/07 to 2018/19 when inflation was benign and interest rates were largely falling.

They are aware of this and do find “evidence of asymmetry, with pass-through tending to be more positive when interest rates are rising”.

But they still claim the impacts on rents of rising rates are small.

However, they note:

Our sample period, from 2006/07 to 2018/19, does not include a period where interest rates rose as much as they have in the current cycle. It is plausible that pass-through could be higher when interest costs rise sharply.

More significant though is that they rule out any “spillover” effects between investors with high mortgages and those with lower mortgages.

This is tied up with their method, which I don’t discuss here.

Effectively, they seek to determine whether those with high mortgages push up rents by more than those with low mortgages when interest rates rise.

They assume that their is no difference in rental setting between the groups, which leads them to conclude that there is “limited pass-through” of higher interest rates into rental inflation.

However, in rental markets investors of all kinds observe the movements in rents in the local areas that they are offering tenancies, irrespective of whether they have borrowed heaps or not.

Investors apply ‘what the market will bear’ logic and if rents start rising in the segment that they have property to offer for rental accommodation, then they will follow each other.

Which effectively negates the methodological validity of the RBA approach.

They dodge this criticism by claiming that in Australia, there are “lots of individual landlords all competing for renters” which suggests these landlords all act in isolation and set their rents without regard to the ‘market rates’ that are applicable to the housing segment they are operating in.

I know people who rent houses and flats.

They are all fiercely aware of the rents that are in the local area and beyond and calibrate their rental decisions accordingly.

Further, many landlords work through a real estate agency who manages the properties for them and effectively sets the rents and probably never really knows how much equity the landlord has in the property.

Conclusion

This is another example of how monetary policy as currently practised is not fit for purpose.

Note:

I am travelling to Manila later today for work commitments and will be away all week.

Depending on my free time, my planned blog post for Thursday of this week may or may not appear.

We will see.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.